FEMA MGT-318 Public information in an all-hazards Incident presents a multi-part “5 Minute Training” for TERT.

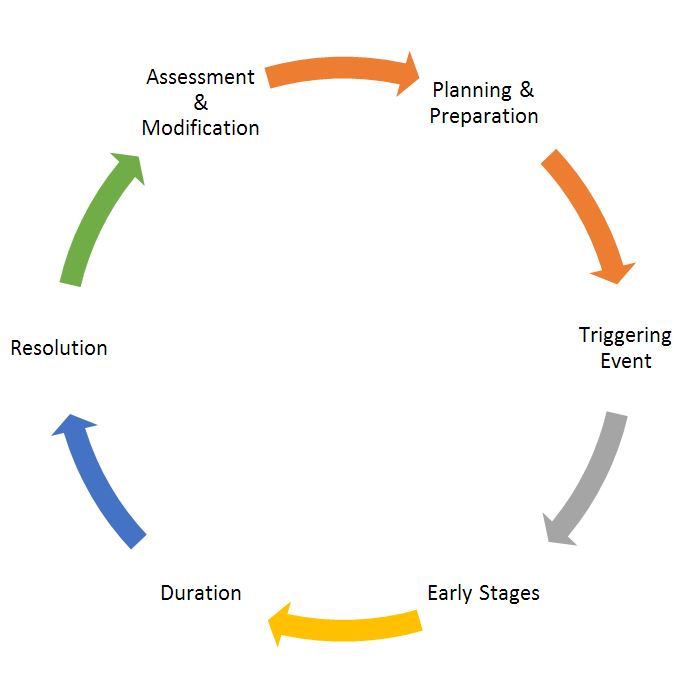

The Communication Life Cycle includes:

- Planning and Preparation

- Triggering Event

- Early Stages

- Duration

- Resolution

- Assessment and Modifications

Every WMD, Terrorism, or all-hazards incident evolves in phases, and communication practices during such an event must evolve in parallel fashion. By dividing the incident into phases, the communicator can anticipate the information needs of the media and the public during each phase.

The figure above displays the typical communication phases that occur during an incident. As an incident progresses through each of these phases, Public Information Officers (PIOs) and their teams should take a series of action steps to ensure that communication efforts effectively reach their various target audiences during each stage.

The role of the PIO and the public information team is critical in helping the response organization navigate through each of these phases and meet the communication objectives within each phase. Therefore, as each phase is discussed, the communication objectives that must be met and the action steps that should be taken will be identified.

Action Steps of the Crisis Communication Life Cycle

Planning and Preparation Phase

Of all the phases that occur during the course of a WMD, terrorism, or all-hazards incident, the planning and preparation phase has the greatest long-term impact on the image and reputation of a jurisdiction. Although no one can predict exactly when disaster will strike or what the nature of the event might be, it is possible to consider the various types of disasters that a jurisdiction might face. A substantial amount of planning can take place well in advance of even unthinkable events.

PIOs can prepare to deal with the media long before an incident actually occurs. For example, preliminary questions can be raised and reasonable answers sought. Initial communication documents can be drafted with blanks to be filled in as circumstances unfold. Spokespersons, resources, and resource mechanism can be identified. Training exercises can take place and plans and messages can be refined. Alliances and partnerships can be fostered to ensure that experts and public officials are speaking with one voice.

The PIO should seek to meet the following objectives during the planning and preparations phase of an incident:

- Accomplish as much incident communication management planning, team training, and resource development/acquisition as possible.

- Implement programs to educate the public and media about the jurisdiction’s disaster response plans, processes, and capabilities.

- Conduct community-relations programs that firmly establish, with internal and external constituencies, the public information function’s emergency response role.

Steps for Planning and Preparation Phase

Steps 1-5

Step 1. Research the various types of incidents.

Examine the ways public information officials have responded to past incidents. What worked well? What did not work well? Learn from others mistakes and successes.

If a crisis communication plan (CCP) has not yet been developed, review CCPs that others have written. Use that information to develop a plan that can be adapted to the local jurisdiction. Leaders of emergency response organizations are looking for written documentation that describes the public information function during a major incident. Such a plan is described in Step 7.

Step 2. Ensure a seat at the EOC table.

Be sure to confirm that the public information function is represented at the EOC and in the emergency planning process. As important as crisis communications are, it is not uncommon for PIOs and other communicators to be overlooked when the EOC staff convenes. Integrating the CCP into a jurisdiction’s overall emergency response plan is critical. A perfect media and public information plan that cannot be executed due to resistance or lack of understanding on the part of response leadership is useless.

A jurisdiction’s leadership must understand that the absence of the public information function during an incident will most certainly create the following circumstances:

- Negative public response

- Conflicting messages from multiple experts

- Delayed release of information

- Lack of reality check on recommendations

- Unchallenged rumors and myths

- Lack of solid communication plan

- Failure to be first source of information

- Neglect of expressing empathy early

- Failure to monitor news media output

Educating emergency managers and the executive leadership will help to ensure that the PIO has a seat at the EOC table, if and when a major event occurs. When interacting with colleagues while preparing for a potential emergency event, consider the following recommendations:

- Dress and behave in a professional manner.

- Be an ambassador of communication. Everyone in the organization who is involved in emergency planning and response should recognize the PIO and know his or her name. Meet informally with planners to discuss ways that the communication team can help them better communicate with the public, the jurisdiction’s partners, and other stakeholders.

- Engage the EOC leadership by proposing straightforward objectives for the public information function to address when an incident occurs.

- Prepare a document for emergency management and executive leadership that explains how the overall response and recovery operation will benefit from committing to and investing in public information activities.

Simply put, any issues or concerns about being overlooked “at the table” during an incident must be addressed during the planning and preparation phase. Do not be reticent about this issue. Talk with emergency operations managers, and cite recent national events to illustrate the importance of communicating with various target audiences.

Note: Many emergency operations managers think “two-way radio” when they hear the word “communication.” Use the terms “public information” to distinguish what the PIO does.

Step 3. Build relationships with the media.

Establishing important media relations in the midst of a WMD, terrorist, or all-hazards incident is virtually impossible. The development of media relations must be an ongoing process before an incident occurs.

Step 4. Prepare collateral materials and an information/media kit.

Should an incident occur, the media will probably request background information about the community, its businesses, and its residents. Prepare packets that include this type of information prior to an incident. These packets should be well-formatted, enclosed in attractive folders, and contain the following.

- Current community information

- History of the community

- Community map

- Hotel accommodations and food service facilities in the community

- Area attractions

- Emergency website address (for media)

- Demographic information

- Business information: types, major corporations, role in the rescue and recovery

- Name and contact numbers for the community PIO

- Names and contact number of subject matter experts, if appropriate

Step 5. Identify partners and stakeholders.

Partners are those individuals and organizations with whom the PIO will work or on whom he or she will depend for support before, during, and after an incident. Partners can include collateral agencies in the local jurisdiction, state and federal agencies, communication service providers, and fellow PIOs. They might be leaders from prominent private sector firms, elected officials, or community leaders.

Stakeholders are, by definition, people from the general public or members of organizations or other specific audiences whose lives are impacted by a WMD, terrorism, or all-hazards incident and its aftermath.

Depending on the circumstances, the news and social medias can function as a partner, a stakeholder, both, or neither. For example, the news media can be a PIO’s partner by helping to disseminate emergency public information when necessary. Similarly, even though a reporter is theoretically an objective observer, the news media will often have a stake in events following an incident.

When establishing partner and stakeholder relationships, identify those local and state businesses that can be of special value to the crisis communication team (CCT) during an incident. Team members should be involved in community organizations and be involved with business and industry associations as well.

Partners and stakeholders should know the members of the CCT. If prominent public figures view members of the CCT as supportive members of the community, they will be more apt to provide support and assistance during emergency situations.

Completing the following tasks before an incident occurs will facilitate initial communication efforts between public information staff and partners and stakeholders.

- Identify the specific role each potential partner and stakeholder should play during an incident. Assess the strengths, weaknesses, and unique abilities that each partner brings to the table.

- Create a partner/stakeholder contact sheet that includes all available phone numbers (work, home, cell, etc.) and all email addresses for those on the list. Obtain permission to contact those on the list by any means necessary during an emergency.

- Draft a plan to facilitate partner/stakeholder communication (including email alerts, twice-daily faxes, conference call, etc.) during an incident that everyone understands and to which everyone agrees.

Identify community leaders and members of institutions such as schools, community organizations, and churches/religious institutions who are willing to support public actions, distribute information, or counter rumors surrounding an incident. These partners may be more influential, more trusted, and more familiar with the target audience than public information personnel. They may also be more able than the media to motivate the public to take recommended actions.

Consider using memoranda of understanding with various partners to engage them as disseminators of information during a public emergency and to supply them with background information prior to, or at the onset of, an emergency. Develop reliable and efficient communication practices to provide these partners and stakeholders with factual information when their constituencies begin to ask questions. Also consider inviting these partners to tour emergency facilities prior to an incident.